History of Psychiatry in Utah

Introduction to the History of Psychiatry in Utah

By Paul L. Whitehead, M.D. and R. Jan Stout, M.D.

Three years before the pioneers entered Salt Lake Valley, organized psychiatry was born in the United States. Ripples of this new medical specialty were felt here in the late 19th century with the opening of the Utah Territorial Insane Asylum in 1885, later called the Utah State Hospital. The first half of the 20th century saw such innovations as insulin and electro-convulsive therapy in the late 1930’s, psychoactive medications in the early 1950’s, and such developments as psychotherapy, child psychiatry, hospital consultation-liaison and behavioral psychiatry.

During the last four decades, psychiatry in Utah as elsewhere has become a major specialty of medicine. There are now over 100 general and child psychiatrists in the state. Almost every large general hospital has a treatment unit designated for psychiatric patients. Private corporations are currently planning major building programs to provide specialized psychiatric facilities. A renewed effort to improve public understanding of psychiatry is underway locally and nationally to help demystify psychiatric disorders and make it easier for those in need to seek help. Psychiatric illness affects 20 percent of our population in a given six month period according to the recent, extensive study by the National Institute of Mental Health. Unfortunately, according to the same study, only 20 percent of those with psychiatric disorders receive any treatment.

This special issue looks at psychiatry in Utah from its early beginnings, through its development, to the current status of this specialty. It concludes by assessing psychiatry’s future as an integral member of the medical community with a special role in bridging the scientific and humanistic aspects of medicine.

Commitment hearings were held weekly, at the General Hospital (later in the Department of Psychiatry). A clerk and judge from the District Court would preside, with two physicians, each of whom received the statutory fee of $5.00 per case. Physicians with psychiatric expertise were few. Dr. John Llewellyn, an internist with a little training in neurology and psychiatry, Dr. Foster Curtis, superintendent of the Veterans Administration Hospital, and Dr. Reed Harrow, pioneer neurosurgeon, often helped. Any other doctor with a smattering of interest was appointed. The patient was usually seen without prior review in the presence of the Court, and the decision whether to commit was made on the spot, with only a few minutes for each case.

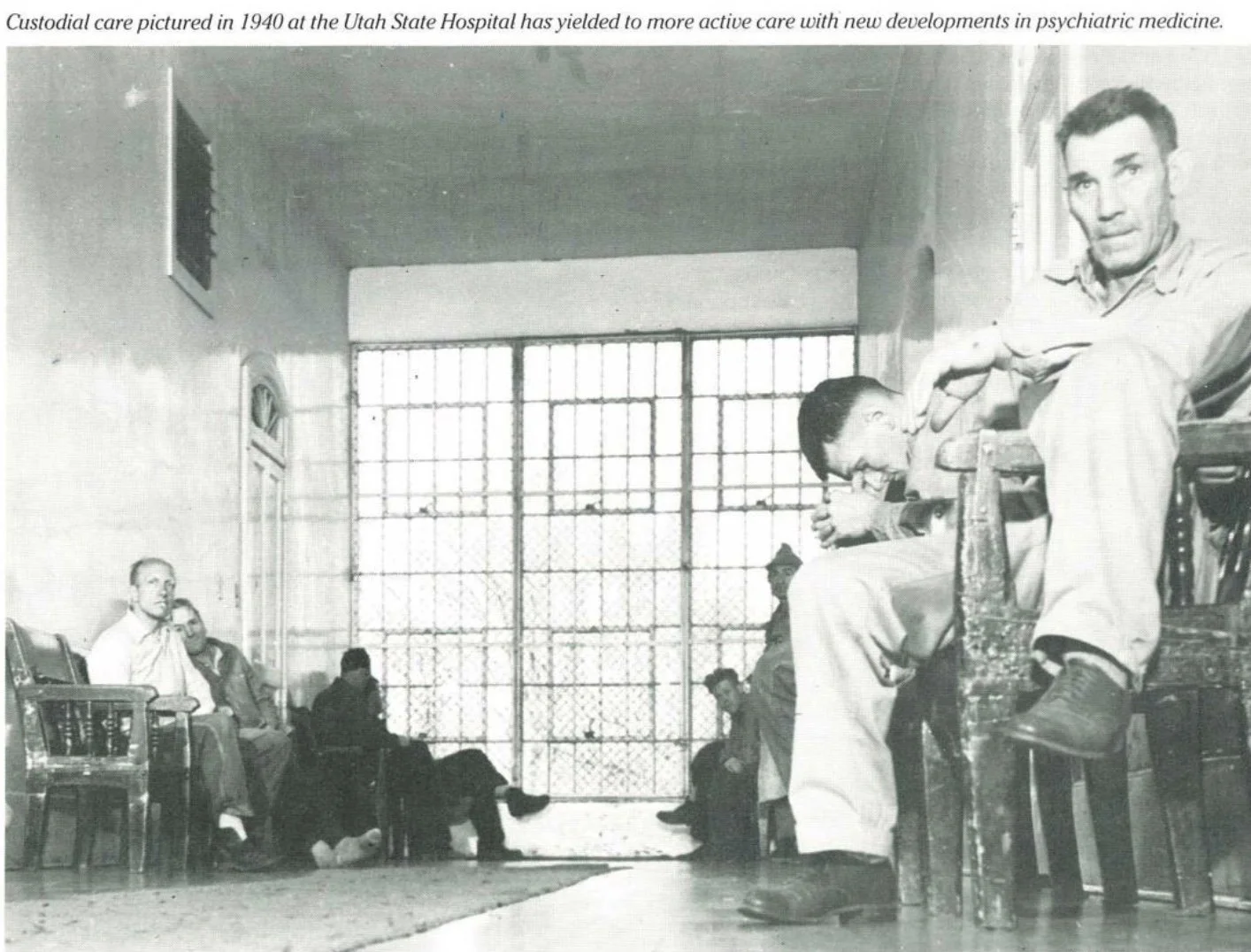

At the State Hospital, custodial care was the major xm. responsibility. Hydrotherapy was a major treatment program, with needle showers for stimulating withdrawn patients and wet pack and special suspension tubs for hours of sedation. Several rooms with iron bar cages were used to keep the criminally insane confined, eliciting the comment of a visiting national expert, “We treat animals better.”

In the late 1930’s, under Dr. Garland Pace, the Hospital moved from compassionate, long-term custodial care to an active treatment philosophy. Manfred Sakel’s new insulin treatment plan for schizophrenic patients was adopted. Physicians were actually TREATING patients scientifically!

The insulin treatment area was a large hall with 40 cots; women to the north, men to the south. Even in coma there was no co-mingling! Six days a week for six weeks, the patients were given regular insulin in doses increasing to 2,000 units, if necessary, to produce coma and sometimes convulsions. If the coma did not terminate spontaneously, transnasogastric orange juice or I.V. glucose was given. Each of us laid claim to an open vein and guarded it jealously! Treatment was dramatically effective in many cases. The mortality rate was one or two percent and some cases had residual neurological damage. The trade-off was considered favorable in the face of such a grim illness.

The expense of that much insulin strained the hospital budget and drained the supply of insulin. There was serious discussion about asking the Diabetic Association to defer casefinding campaigns, to put less demand on the limited supply. The federal government took notice of competing demands and required meat packing plants above minimal size to save the pancreases for insulin extraction.

When the seizure was deemed the therapeutic part of the process, other methods of inducing seizures were tried. In Europe, camphor was injected intravenously for this purpose (venous thrombosis limited the number of injections). A more sophisticated form of camphor, a cardiac stimulant Cardiazole (Metrazole in the U.S.) replaced camphor. The patient could usually be persuaded to take the first treatment but it took six men to persuade him to come for the subsequent sessions. Then electroshock therapy (EST) largely replaced other somatic modalities.

Dr. Owen Heninger, who followed Dr. Pace, introduced the Maxwell Jones Therapeutic Community Model to the Hospital; the milieu became the therapeutic process. Somatic treatment programs were relegated to the Dark Ages Museum along with chains, bars, dunking stool, insulin and EST as used at that time. The Hospital received national awards for the innovative program.

Other forces were bringing profound changes in the psychiatric scene. The development of private hospital facilties, the introduction of effective psychotherapeutic medications, the increasing number of private psychiatric practitioners available, the establishment of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Utah School of Medicine, the shift of emphasis to the Community Mental Health Centers and the changing patient population from chronic thought and mood disorders to the character disorders all contributed to the successes of the Therapeutic Milieu model at the State Hospital. These shifts also made possible the decimination of the census of the State Hospital from about 1350 in the early 1950’s to under 300 patients during the next decade. Some activists believed that mental illness could be eliminated entirely by eliminating the State Hospital.

Many patients thought to have intractable illnesses unresponsive to other available treatment were considered candidates for the newly developed transorbital lobotomy. While there is no record of these being performed in the State Hospital, over 500 were performed on private patients in Utah in the 1940’s. A few of the more sophisticated psychosurgical procedures, such as the Grantham operation, were performed.

While at the University Medical Center, Dr. Peter A. Lindstrom, Professor of Neurosurgery, developed the Prefrontal Sonic Treatment. This was dramatically effective for some cases of intractable depressions, obsessive-compulsive disorders, certain phobic conditions, and some psychosomatic disorders, with little psychological damage. Unfortunately, it was thought to be a form of lobotomy and did not receive the professional support it warranted.

Dr. C. H. Hardin Branch organized the College of Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry and became its first chairman in 1948. Through his able leadership, communication skills, affability and clinical expertise many physicians were trained in the specialty of psychiatry. He provided strong impetus to the growth of psychiatry in Utah and was later elected President of the American Psychiatric Association.

In the mid-1950’s, the community mental health center concept became the wave of the future. Notwithstanding all the wonderful goodies promised, the State Legislature was very cautious in passing enabling legislation. Opposition came from anti-mental-health persons fearful that psychiatrists were in league with the Kremlin, receiving weekly orders from Moscow, and were a bunch of atheists. Some thought that psychiatrists were plotting a “take-over-day” to commit the officials of the state government, from the Governor and Attorney General on down, to do lobotomies and/or EST on them to establish political control. Only by a compromise was the legislation passed, having to include a paragraph that no one working under the bill was permitted to change anyone’s belief in God (even if the patient believed he were God).

Remarkable progress has been made in the field of psychiatry. We are proud of the accomplishments made by many dedicated psychiatrists and other mental health professionals in Utah.

Notes on the History of Psychiatry in Utah

By Louis G. Moench, M.D.

Until the last four decades, the treatment, care and custody of the mentally ill was largely a family or a state responsibility, even though state medicine was an epithet. Psychiatry lagged far behind other medical specialties in public acceptance. Freud’s theories on sexuality raised fears that psychiatrists advocated sexual license as a cure-all.

Establishment of asylums (in the good, old meaning) removed many patients from back bedrooms or under bridges and put them where they could receive long-term care for long-term illnesses. Location of state institutions in the West followed a typical pattern. The prison, which furnished the most jobs for local residents, was usually “given” to the city with the greatest legislative clout: Carson City, Nevada; Salt Lake City, Utah; Boise, Idaho; Rawlings, Wyoming. The State Insane Asylum and the Training School vied for second and third place. Hence, the location of the asylums in Provo, Reno (Sparks), Blackfoot, and Evanston.

With use, psychiatric terms became derogatory and feared so they were changed: “manic-depressive” became “bipolar affective” and state insane asylums became state hospitals.

Voluntary patients were accepted, but court commitment was the common mode of admission to the Utah State Hospital. In the Salt Lake area, the old General Hospital served as the holding facility for involuntary patients awaiting court hearings. Two rooms in the basement were designated psychiatric rooms, with thick, bare stone walls, cement floors and heavy metal doors. Rooms had tiny observation windows through which the first floor nurse would occasionally look gingerly, and flaps at the bottom of the doors to permit sliding a dinner tray into the room without opening the door. Dr. David Young, observing the rooms on his initiation tour, was invited to comment: “It sure looks sturdy!”